“My father was so enamored of this beautiful, gentle plant, that he tried to keep it in the New Mexico high desert.”

Tree Hair:

Native Americans named Spanish Moss Itla-Okla or “Tree Hair” because of it’s springy, stringy quality. Post conquest, the French and Spanish created new, retaliatory names for it that mildly insulted one another’s beards and hair, and since the French outlasted the Spanish in in what is now the Southern US, “Spanish Moss,” is the title that ended up sticking — one of many examples of things being re-named as cultures collide, and of the European conquerors’ propensity to mis-label things. Not only is itla-okla not Spanish, it’s also not a moss. Rather, it is a “bromeliad” related to the pineapple and the succulent.

Spanish Moss is an air plant. It has a remarkable ability to trap water in its scaled leaves until it’s needed; the leaves turn green when they’re full and grey when they’re empty. The seeds of the plant either float through the air, or festoons are brought to new places by birds or wind, until they find the right healthy tree in a swamp where they can grow — not as parasites, but just parked there, borrowing the structure.

Once upon a time, Spanish Moss was everywhere in the American South. It was so bountiful that it was used for tinder, to stuff mattresses, to weave blankets and rope, as garden mulch and even as a component of the mortar of houses; commercial use peaked in the 1930s depression before synthetics took over. Animals, including bats, insects, frogs, lizards, and jumping spiders, make their home in the “moss,” and birds like yellow-throated warblers and northern parulas use it to make their nests. When my aunt (my father’s sister) lived in Albuquerque, NM she would carry it home from visits to Louisiana in her suitcase and drape it around her apricot tree when she had mardi gras parties.

A Canary in a Coal Mine

Itla-Okla may be quite versatile, but it was almost made extinct in the Southern US in the twentieth century by chemical plant pollution. Air plants can’t survive without air. Happily, it has come back somewhat in recent years, as the fumes have abated. This is thanks in large part to good samaritans who worked hard to keep it going during the tough times of the 1960s and 70s. One such good samaritan was a friend of my father’s from Baton Rouge. Fred had had polio as a child and he spent most of his time in an iron lung. When he was out and about, though, he would gather what moss he found and drape it around his home, in the lower pollution suburbs. Fred was a lovely man, and I guess he could relate to the plant’s plight, as they both struggled to breathe.

Southern Seasoning

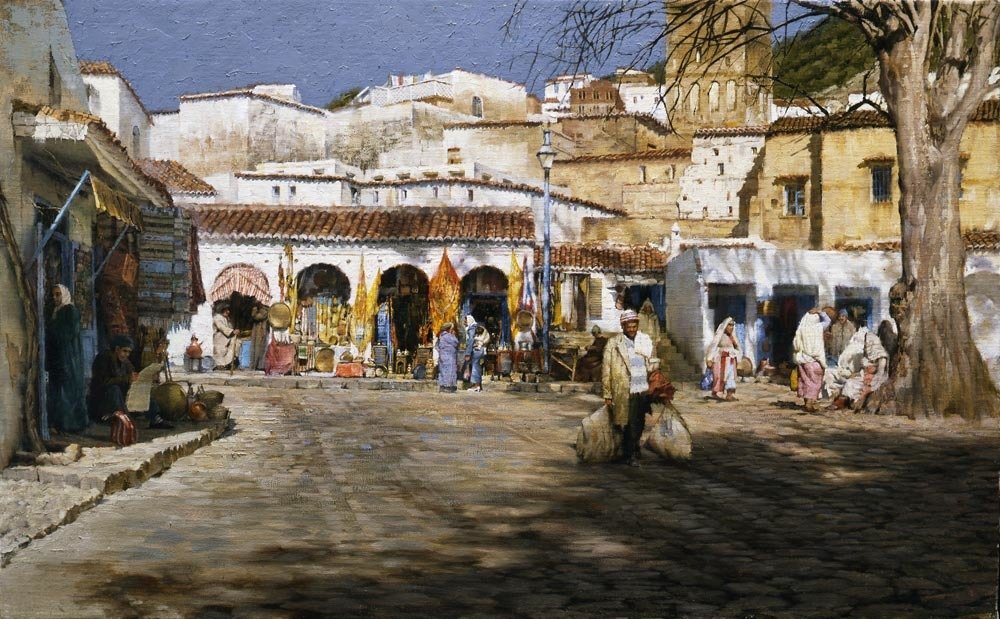

My father loved Spanish moss. It’s subtle, silvery drapery creates fantastic atmosphere and “…gives the Louisiana landscape its mood of softness and mystery…”— Clark Hulings, A Gallery of Paintings. For an artist who built compositions from the ground up, starting with the largest elements and adding ingredients to complete the scene, Spanish moss was the equivalent of salt and pepper—spices to sprinkle strategically to increase ambiance and further pull in the viewer. It helped him place us right into the painting.

My father was so enamored of this beautiful, gentle plant, that he too tried to keep it in the New Mexico high desert, which, of course, did not work out. Neither he, nor his sister could keep it alive in the dry air. While it lasted, it was an ethereal reminder of Louisiana and his friend Fred.

Do you have a Spanish Moss story, or a Louisiana memory to share? We’d love to hear about them.